Women Dresses India Biogarphy

Source(google.com.pk)As Islam reached other lands, regional practices, including the covering of women, were adopted by the early Muslims. Yet it was only in the second Islamic century that the veil became common, first used among the powerful and rich as a status symbol. The Qu'ranic prescription to "draw their veils over their bosoms" became interpreted by some as an injunction to veil one's hair, neck and ears.

Throughout Islamic history only a part of the urban classes were veiled and secluded. Rural and nomadic women, the majority of the population, were not. For a woman to assume a protective veil and stay primarily within the house was a sign that her family had the means to enable her to do so.

Since nomad women rarely veiled, in the early stages of those Islamic countries with nomadic roots, women often were allowed to go unveiled, even in town. In the years of the early Safavid dynasty, women were unveiled, although the custom was changed by late Safavid times. Among the Turks, who came into Anatolia as nomads, Ibn Battuta in the fourteenth century saw what he called a "remarkable thing. The Turkish women do not veil themselves. Not only royal ladies but also wives of merchants and common people will sit in a wagon drawn by horses. The windows are open and their faces are visible."The Middle Ages

The veil did not appear as a common rule to be followed until around the tenth century. In the Middle Ages numerous laws were developed which most often placed women at a greater disadvantage than in earlier times. In some periods, such as under the Mamluks in Egypt, repeated decrees were issued, urging strictness in veiling and arguing against the right of women to take part in activities outside their home. One commentator, Ibn al-Hajj, claimed this was a good thing because a woman in Cairo would "go out in the streets as if she were a shining bride, walking in the middle of the road and jostling men." He cautioned shop keepers to be careful when a woman came in to buy, "for if she was one of those women dressed up in delicate clothes, exposing her wrists, he should leave the selling transaction and give her his back until she leaves the shop peacefully..."

The Nineteenth Century

By the second half of the nineteenth century, intellectuals, reformers, and liberals began to denounce the idea of women's protective clothing. This group was sensitive about the advances western nations had made, and wanted to push their countries toward a more western-style society. One way of achieving this, they felt, was to change the status of women. To them this meant abandoning traditional customs, including protective covering and the veil which they saw as a symbol of the exclusion of women from public life and education.

In the early years, men were in the forefront of this effort. Qasim Amin, who in 1899 wrote The Emancipation of Woman, called for new interpretations of the Quran with regard to limited divorce, polygamy, and wearing the veil. He argued that such practices had nothing to do with Islam, but were a result of customs of peoples who had become Muslims. Enormous debate followed his work. Some of his detractors were women. Egyptian writer Malak Hifni Nassef worried about women "moving from that dark and familiar state" before they were ready. She said that first women needed a "true" education and better knowledge of the world, and men needed to learn not to harass unveiled women. She resented men telling women what they should do: "If he orders us to veil, we veil, and if he now demands that we unveil, we unveil. There is no doubt that he has erred grievously against us in decreeing our rights in the past and no doubt that he errs grievously in decreeing our rights now."

The Impact of Nationalism

The ideas of Qasim Amin reflected those who closely linked the emancipation of women and rejection of veiling to national movements for independence. For this group, the changing roles of women in society were important ways to convince the overseas colonial rulers that their subject nations were ready to govern themselves. Women were encouraged to be symbols of the new state. Those who resisted these ideas of social progress were mocked. Turkish elites, for example, mocked women covered in black, calling them "beetles." Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, who began to build a secular nation-state in 1923, denounced the veil, calling it demeaning and a hindrance to civilized nation. But he did not outlaw it. Shortly after, in Iran in the 1930s, Reza Shah Pahlevi did, issuing a proclamation banning the veil outright. For many women, this decree in its suddenness was not liberating but frightening. Some refused to leave home for fear of having their veil torn from their face by the police.

Male leaders of nationalist movements encouraged women to join them and appear more freely in public. Slowly some women did. In 1910, a young Turkish woman attracted attention by daring to have herself photographed. At about the same time, educated women in Turkey began to leave the house unveiled, but still wearing hijab. The most dramatic public unveiling was undertaken by Huda Shaarawi in Egypt in 1923. Following suit were Ibtihaj Kaddura in Lebanon, Adila Abd al-Qudir al-Jazairi in Syria, and much later Habibah Manshari in Tunis. Moroccan scholar Fatima Mernissi remembers the fight her mother had with her father about replacing her heavier traditional veil with "a tiny triangular black veil made of sheer silk chiffon. This drove Father crazy: 'It is so transparent! You might as well go unveiled!' But soon the small veil, the litham, became the fashion, with all the nationalists' wives wearing it all over Fez - to gatherings in the mosque and to public celebrations, such as when political prisoners were liberated by the French."

Women's organizations also played an important role in transforming dress, although this was a minor issue in their struggle for women's political rights and for legal reforms. It should be stressed that for many women it was not the fact of wearing the veil that was the issue, but that the veil symbolized the relegation of women to a secluded world that did not allow them to participate in public affairs...

Revival of Hijab

As the century progressed, a revival of veiling and introduction of more modest dress reasserted itself. Opposition to Islamic required clothing had never been truly universal. Among the lower middle classes it had always tended to be defended in the face of change. Even in Turkey where the state had pushed the idea of reform, new ideas and styles of dress did not reach women in the hinterland.

In areas where Islam was resisted and believers felt threatened, like Indonesia and the Philippines, Muslim women began to dress more conservatively as a way to assert who they were. During militant struggles for independence, such as that against the French in Algeria or the British in Egypt, some women purposely kept the veil in defiance of western styles. It meant they also could take part in veiled and silent demonstrations, or could hide weapons under long robes.

There were other reasons for taking up and defending hijab. One was the growing reaffirmation of nation identity and rejection of values and styles seen as western. In response to Egypt's catastrophic loss to Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War, and the seeming failure of secularism, there also was a push to return to Islamic laws which had been abandoned. Modernization was seen as negative, a phenomena which encouraged people to reject not only Islamic but all indigenous traditions. Wearing hijab came to symbolize not the inferiority of the culture in comparison to western ways, but its uniqueness and superiority.

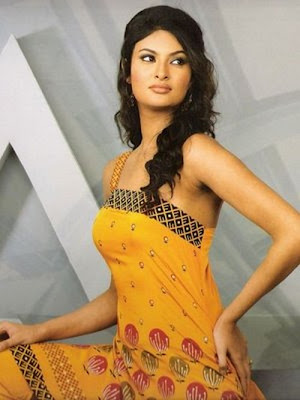

Women Dresses India

Women Dresses India

Women Dresses India

Women Dresses India

Women Dresses India

Women Dresses India

Women Dresses India

Women Dresses India

Women Dresses India

Women Dresses India

No comments:

Post a Comment